Welcome to Modal-Improvisation.com!

Welcome! You can view here the new video Teaching Monophonic Modal Improvisation in the Western Music Classroom. You will also find several articles on improvisation and information about modal improvisation workshops. Enjoy, and please drop us an email at info@modal-improvisation.com if you would like to be informed when additional videos and written materials have been posted. Thanks, Ken Zuckerman

(4-minute Trailer) Teaching Monophonic Modal Improvisation in the Western Music Classroom

Here you can watch a 4-minute Trailer of this new documentary. Please scroll down to watch the full 30-minute video.

Video: Teaching Monophonic Modal Improvisation in the Western Music Classroom

This is the full 30-minute video of Teaching Monophonic Modal Improvisation in the Western Classroom.

Improvisation Workshops

Ken Zuckerman’s extensive research into the practices of improvisation in both western and eastern music have given him a unique perspective on teaching this subject. For example, his courses at the Music Academy of Basel on “Modal Improvisation” use the source material of Indian melodic modes (ragas), and rhythmic structures (talas), to initiate western music students into the techniques of improvisation. Students usually first learn these basic skills vocally and then later, apply them to their instruments

Many of the basic skills of Indian music can be of great value to any western music student. Workshops in Modal Improvisation focus on several of these basic concepts and skills:

- introducing a monophonic music system that is based on highly differentiated modal hierarchies

- exploring the rules and strategies of improvising within specific modes (ragas)

- concentrating on melodic and rhythmic ear training exercises which are not usually a part of western music courses

- learning all of these skills by means of a fundamentally different system of music pedagogy: unwritten, aural tradition from the East.

Within a surprisingly short period of time, the students gain a basic understanding of the basic Indian modes and make their first attempts at improvising within the rules of several raga hierarchies. They also significantly improve their ability to listen to increasingly complex melodic and rhythmic phrases, internalize them and then repeat them in the moment.

Why Learn Improvisation

or…

Does the Study of Improvisation belong in a Music Conservatory?

“Improvisation” is one of those words that has a place in almost any context, from cooking to crafting, sewing to storytelling, poetry to comedy, dance to drama, and mime to music. It also encompasses a wide spectrum: from classical to folk, western to non-western, and amateur to professional. We can think of improvisation as both a skill acquired during many years of study, and as an action that is “just felt” in the moment. In short, improvisation is a big subject and plays a role in almost everyone’s lives.

During most all of the important periods of our music history, from the modal improvisations of medieval chant, to the extensive art of diminutions during the Renaissance, to the virtuosic cadenzas of solo concerti, improvisation was looked upon as an important measure of a musicians ability. In addition, composers throughout history have used improvisation as a tool for developing musical ideas and to help set an atmosphere for inspiration and creativity.

But as important a skill as improvisation once was for musicians, today it is rarely an integral part of a music students’ education. Rather, the word improvisation now usually calls to mind music styles outside the realm of a conservatory – styles like jazz, blues, and non-western traditions. Although in recent years there have been some attempts to integrate improvisation into some of the more “experimental” compositions, it remains nevertheless, a skill that is rarely called for in the repertoire that most conservatory trained musicians are required to perform.

But if composers and performers throughout history used improvisation extensively during the creation and execution of music, how can it be that it is not an integral part of music education today?

In fact, improvisation is still an important skill for any musician, and making it a part of a conservatory curriculum can have a beneficial result in many aspects of a students’ musical development. From technical skills, to ensemble playing, to memorizing pieces more quickly, to analysis and interpretation, learning to improvise sharpens many of a musicians’ skills and even trains new abilities that may otherwise never develop. For instance, it gives a performer an instant taste for composing, and in performance, can help develop a stage presence that is more relaxed and which enables one to react better in the moment. Whether to bring in an element of spontaneity, or just to recover more quickly from a mistake or lapse of memory, the ability to improvise is beneficial to all aspects of musicianship.

Let us look again briefly at the subject from several perspectives: historical, pedagogical, and purely musical.

Historical – As mentioned above, in our western music tradition, improvisation was once an important part of a musicians training and was used extensively in performance. From the medieval periods onwards, both composers and performers were often times cited as being fluent improvisers, able to leave their listeners spellbound during long passages of improvisations. Virtuosic violinists used to show off their skills at improvisation during extended extempore cadenzas. Beethoven was a master of improvisation and was said to have even been able to improvise fugues (regularly won contests in improvisation.) Chopin and Liszt were also known for their improvisatory skills. Its prevalence alone as an important skill is a good reason for musicians today to at least have a taste of this practice. Whether or not a student becomes a master of improvisation, it also gives him/her both a direct link to, and a common thread of experience with, performers and composers from past epochs and musical styles.

Pedagogical – The study of improvisation builds musical skills that cannot be learned as well by other methods. Improvising develops a part of the musical intelligence that has nothing to do with reading notes or attempting to execute one fixed interpretation of a composition. In addition it involves learning a process of immediate listening, analysis and execution, which goes far beyond the usual skills developed in ear training classes. Improvising develops not only a quicker kind of instant listening, but also helps develop a feedback mechanism that sharpens a musicians ability to react in the moment and build upon the music being developed. It is also an excellent measure of a students’ understanding of the compositional elements of a given style. Combined with analysis and practical exercises in composing, improvisation may be thought of as one of the highest measures of a students’ complete understanding of a given style.

Purely musical – There are indeed, many convincing reasons why all music students should learn to improvise. Perhaps the most important is that improvisation, both by composers and performers, played an important part in the performance of much of the music that is still heard in concert halls today! But in addition to all the justifications and benefits- technical, compositional, etc. – there is an additional reward that is purely musical in nature – and hard to resist. Once learned, improvisation is actually fun and gives a musician an additional sense of satisfaction in participating in the creation of music in the moment!

San Rafael, California September 1, 1995.

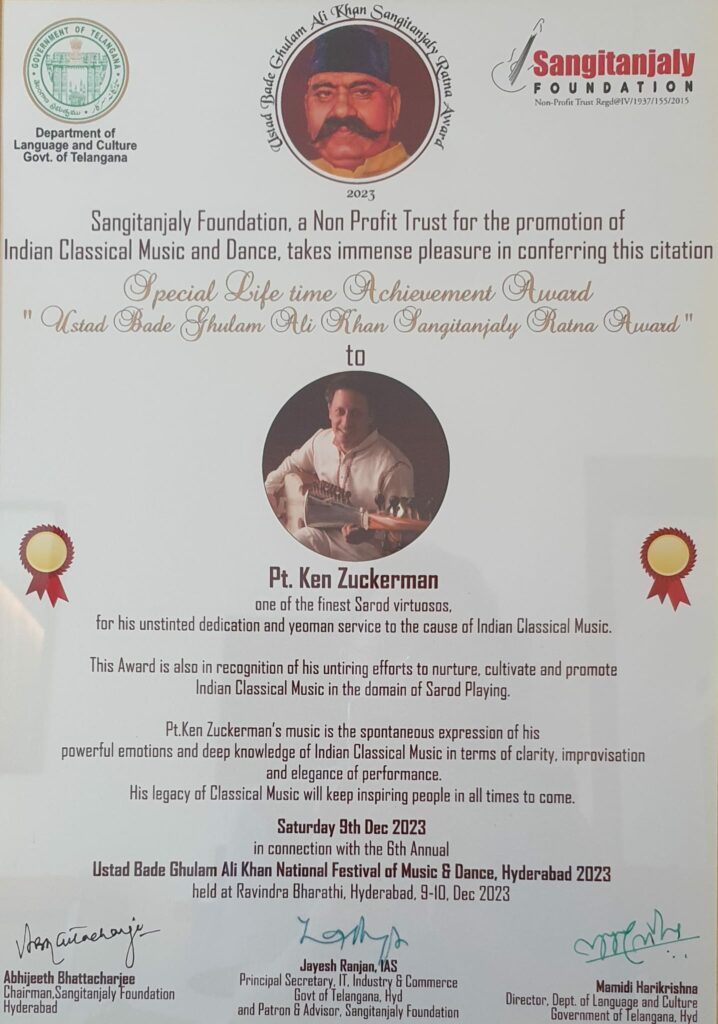

Ken Zuckerman teaches improvisation courses in Medieval music and the classical music of North India at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Hochscule für Musik, and Musikschule of the Music Academy of Basel. He is also the director of the Ali Akbar College of Music – Switzerland.

III. Medieval Music Improvisation Models

Recent research has shown that improvisation played an important role in Medieval music. The study of both theoretical treatises and the music sources themselves, indicates an extensive non-written, improvised tradition, existing alongside the composed, written repertoire. In particular, the 14th-century instrumental collections of estampies and istampitas give us a diverse and instructive glimpse into the medieval world of mode and improvisation. In showing a very consistent conception of modal composition and a diverse employment of improvised structures, they invite us to expand our understanding of the medieval art of melody making.

In attempting to recreate the practice and pedagogy of medieval improvisation, it has been necessary to re-evaluate many of the basic conceptions that have become deeply ingrained in the world of Western classical music education and performance. This has not only involved a different look at the basic materials — i.e. notation, compositions, etc. — but also a look to other musical cultures. In particular, the strictly controlled practice of modal improvisation in North India has provided important clues as to how an extensive unwritten repertoire can evolve.

In addition, it is necessary to take a closer look at the elusive term “improvisation”. Although it is a common word, used to describe a variety of experiences in our everyday lives, its specific meaning in relation to music is often times vague and invites misunderstandings in both musicians and listeners alike. This is easy to understand once we realize that although some aspects of improvisation can be analyzed and quantified, much of the essence of both its internal workings and external “charm” remain, if not completely subjective, at least very personal and rather difficult to put into words. Musicians sometimes describe the process as being mysterious, unconscious, spontaneous, and many are not quite sure why it is sometimes effortless, other times difficult, and in any case, impossible to maintain for extended periods. But on the other hand, almost all musicians acknowledge that it requires a long and extensive practice in order to become a fluent and intelligent improviser. And in general, although some western musicians have had experience with improvisation, it remains nevertheless on the fringe of western music practice and education. This is easy enough to understand since there is little place for it in most all of the repertoire a classically trained musician ever performs. But in the field of early music, where improvisation is know to have played a much larger role, the lack of knowledge and experience is felt much more acutely. Thus the questions emerge, What was the nature of improvisation in earlier times? How were musicians trained in this art? and, Can one ever hope to incorporate this “spontaneous” practice into the “reconstruction” of medieval music?

One of the first things we notice about the teaching of music in eastern cultures is the importance of the teacher. The transmission of music in unwritten, improvised traditions is completely dependent on a close and long-term relationship between the teacher and student. The teachers’ role is not only to instruct in technique, interpretation, composition and improvisation, but also to literally pass on an entire repertoire to the student, without relying on written materials. Thus it is not uncommon in a tradition like classical Indian music, for an apprenticeship to last for over 20 years! The nature of this kind of long-term relationship demands a student to make many adjustments in attitude, not the least of which is a sense of patience that in order to learn the repertoire and become a master of improvisation, it is necessary to spend many years of training, carefully following the example of the teacher.

Another problematic aspect of this kind of music training is the necessity of learning all of the music by ear and retaining one’s entire repertoire in the memory. This is something particularly difficult for us to accept, coming from a tradition where even a performance repeated numerous times is usually not memorized. And this is also an excellent example of an idea which cannot be understood at all without experiencing. For until one learns a large amount of music by ear, and at the same time, commits it to memory, it is impossible to imagine having instant access to so much material while improvising. Even using the somewhat crude example of the computer can illustrate this. Anyone who has had experience with these machines knows how fast the internal memory of a computer functions, as opposed to how much slower it is when one has to put in a separate diskette for each file. In the same way it is easy to imagine how much faster one could access an entire repertoire if it was in the internal memory (the brain) instead of on diskettes (music notation). Even many students of Indian music rely extensively on written notations and in general do not memorize half the compositions which are taught to them. The teacher, while not expressly forbidding the taking of notes, often gives warnings about the consequences of this practice. “Very good! Now after ten years your notebooks are full of thousands of compositions I have given you. But what do you really know? Remember, you can’t bring your books with you onto the concert stage.” My experience of the truth of this statement has left me with the conviction that without learning a given repertoire in this way, it is useless to think that one can develop the ability to improvise fluently and spontaneously in it. For those taking up a study of early music, this is a difficult prerequisite to accept, especially for those who have already received an extensive training in western music.

One of the most difficult problems that faces a western student wanting to learn music in the “classroom of the east”, is the unwillingness to accept the limits of the participation of the intellect during the training. This is not to suggest that a mature player does not think at all when he improvises. On the contrary, there is an important place for active thought while improvising and composing in the moment. However, there is a general tendency for us in the “western world” to over-analyze and to attempt to understand aspects of music making with the intellect which must be first understood at other levels, such as the motor centers and emotions. It is a curious contradiction. On the one hand, we don’t seem to mind at all giving a child all the time he or she needs to learn to walk and run without any intellectual instructions, nor does the child ask for any. On the other hand, when it comes to a beginner in music, whatever his or her age, we insist on explaining many things which can only be understood and executed after much practice. Not only does this intellectual approach actually slow the more important process of intuitive and automatic learning, but it interferes with the students’ developing higher levels of listening and observation. Especially at more advanced levels of learning, it is precisely the moment of not understanding which should sharpen the students’ power of listening and observation – and not simply the impulse to formulate another question. My teacher has struggled with this characteristic in his students for years. At one point, in his usual way of “improvising” analogies to get a point across, he said: “It is really so simple. Why all this talk? When you eat, you eat. When you sleep, you sleep. So – when you learn music, learn music! Why talk?” For most of us, these true, simple and practical words are very difficult to put into practice.

The understanding of mode may be the most important single skill for a musician learning to improvise in Medieval music. It is also an area which is most often completely lacking in the training of musicians today. Although there is an extensive literature in which mode plays an important role, we have very few indications of how mode and modal improvisation was taught during the Middle Ages.

(…)

In Indian music thousands of modal frameworks exist under the general term raga. Many times there are a large number of ragas which share the same “parent” scale – like dorian – but each one has its own distinct identity and rules for composition and improvisation.

(…)

One of the most serious problems in improvising medieval or for that matter, any music, is that the basic rhythmic and melodic building blocks are not an integral part of the musical consciousness. All of these elements must be second nature – automatic, so to speak. If the mind must be concerned with all these small details, then it cannot be free to listen and develop a larger structure. This phenomenon can be compared to language: if we try to think separately of every word as we are speaking, we experience how difficult it becomes to keep a larger concept clearly in mind. Further, if we had to be aware of every single letter of each word, it would be practically impossible to recite a sentence, let alone improvise the re-telling of a story! For a musician trying to improvise in the medieval style today, the problem is extreme. Not only is he cut off from the roots of the style, but often times he has already been exposed to and performed in repertoires as diverse as those of the renaissance, baroque, classic, romantic, avant-garde, pop, rock, etc. When it comes time to improvise, all of these styles and formulas tend to get mixed up and the resulting improvisation has no identity at all!

(…)

On the subject of permutations, there are an almost endless number of ways to approach the multi-faceted subject of improvisation – stylistic, psychological, motor, aesthetic, etc. This variety is in fact, quite in tune with the subject itself! What has been intended here is an introduction to an approach developed somewhat by chance – an encounter between one musicians’ general fascination with the subject of improvisation, and his specific investigations into the musical worlds of India and that of the Middle Ages.

Kenneth Zuckerman

February, 1994 Basel

The above is an excerpt of two articles that can be found in publications from Amadeus Verlag / Winterthur:

German version – “Improvisation in der mittelalterlichen Musik”, Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis Basel / 1984

English version – “Improvisation in Medieval Music”, Improvisation Winterthur / 1995