Sample Program

Mode in D (Dorian)

Anonym – Natali regis glorian (Conductus, 12th c.)

Ken Zuckerman – Composition and improvisations in dorian mode

Gregorian chant – “Universi qui te expectant” (gradual)

Traditional Indian – Raga Bhimpalashri

Mode in C

Traditional Indian Raga “Pahari”

Gregorian chant “Alleluia, Angelus Domini”

Traditional Indian * Raga “Manj Khammaj” – introduction

Jehan de Lescurel (beg. 14th c.) “Bont’s, sen, valours et pris” (ballad, lydian)

Traditional Indian ** Raga “Manj Khammaj” – continued

Traditional Indian/Persian tabla/zarb – solo

12 Traditional Indian ** Raga “Manj Khammaj” – conclusion

Mode in F (Lydian)

13 Traditional Indian ** Raga “Bihag” – introduction

14 Raga “Bihag” – continued and conclusion

15 Anonymous Istampita “˜Principio di virtu”

(source: London, British Library, MS Add. 29987)

16 Jehan de Lescurel “Douce amour, confortez moi” (virelais)

Mode in E (Phrygian)

17 Sephardic “Ven querida”

18 Traditional Indian ** Raga “Bhairavi”

19 Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) “O splendidissima gemma”

20 Traditional Indian ** Raga “Bhairavi”

21 Raga “Bhairavi” – continued

22 Raga “Bhairavi” – conclusion

The musical traditions of the European Middle Ages and of North India, in spite of their many differences, have common roots going back far into the past. This can be seen especially in the organization of compositions according to the melodic modes. Internationally renowned specialists from the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis and of the Indian classical tradition here build a musical bridge between these cultures. Structure and improvisation, sensual melodies and complex rhythms, virtuosity and passion mark this fascinating meeting of two worlds!

This program offers a rare opportunity to experience two different musical worlds in dialogue: the reconstructed musical culture of the European Middle Ages, and the ancient but still continuous tradition of North Indian classical music – two worlds that are indeed separated with respect to time and geography, and yet still linked by common characteristic features. The classical tradition of North Indian music, whose origins can be traced back to antiquity, is marked both by a strong adherence to its own origins and an openness to influences from other cultures. The forms that are still practiced today emerged from a fusion of Hindu and Islamic traditions, which reached their greatest blossoming in the sixteenth century during the reign of the Mogul emperor Akbar (1556-1605). North Indian music is based on the creative interplay of raga (melody) and tala (rhythm). The largely improvised performances are based on both complex melodic models and traditional compositions, which are passed down over generations from teacher to pupil. A delicate balance is always maintained between the proportion of improvised melodic and rhythmic expressions and the given modal structures and rhythmic cycles. This interplay between the traditional frameworks and the spontaneous expression also enables an active dialogue with the listener, who is subtly led through both the familiar and unexplored territory of the modal and rhythmic landscape.

European art music of the Middle Ages, seemingly far removed and accessible only by means of written documents, has clearly recognizable roots in Eastern traditions. So it is not surprising that parallels can also be established with Indian musical culture. In both cultures, the music is based on complex structures. On the performance level, too, there is clear evidence – as in Indian music – of individual creativity through improvisation. In addition to this there is the mutual characteristic of tonal organization, since a central organizational feature of both musical traditions are the melodic modes, through which structural tones, characteristic phrases, and to a certain extent even emotional content, is developed. Although the tonal systems are different (roughly stated: seven whole- and half-tone steps in Western music as compared to microintervals and groups of tones in Indian music), common features can however, be recognized in the means of musical fashioning. In the music of the Middle Ages, too, there are subtle nuances that can bring about highly differ- entiated effects, as Dominique Vellard demonstrates in the heartfelt songs of the 14th century Parisian musician Jehan de Lescurel. Even the so-called Gregorian chant knows emphatic moments, as the offertory Universi qui te expectant and an Alleluia demonstrate. And the intense relationship between music and text is highlighted in both the simple Sephardic song Ven querida and the expansive song of praise to Mary by Hildegard von Bingen.

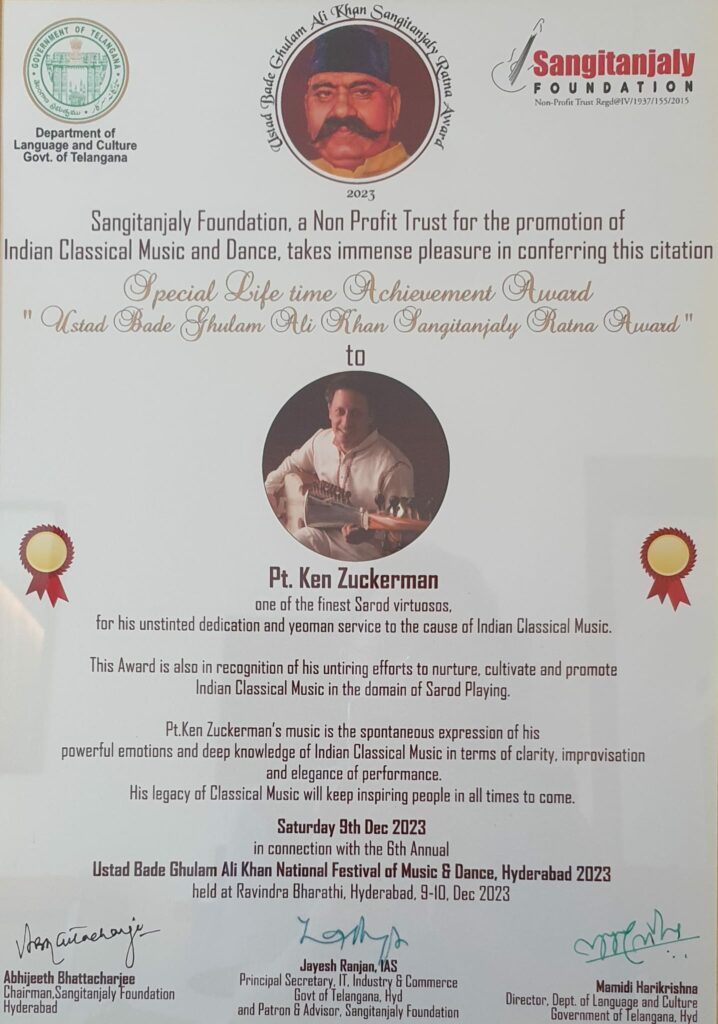

Ken Zuckerman embodies the connection between the two worlds in that he performs on both the Indian sarod as well as the medieval plectrum lute (tracks 2, 15, 16). Both the composition and improvisations in Dorian mode (track 2) and the Istampita (track 15), with their strong modal orientation and repetitive structures, offer ideal opportunities for improvisations that correspond to the Indian examples. In addition to the two great cultural worlds of the Western Middle Ages and classical Indian music, a meeting between the related traditions of the Persian and North Indian regions takes place. Here Swapan Chaudhuri and Keyvan Chemirani contribute significantly not only with their rhythmic accompaniments (tabla and zarb), but also during inspiring solos and duets, as can be heard on Track 11.

In their respective musical development, Dominique Vellard and Ken Zuckerman have each been strongly influenced by a variety of experiences with Eastern music traditions. The Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, where both teach in the medieval program, became the meeting place where they were able to compare notes and develop an organic approach to experimentation. The object of the present recording is to give listeners an opportunity to hear the similarities and contrasts between these two rich musical worlds, as well as to initiate a dialogue between them. In order to realize this goal, some compromises regarding the strict forms of each tradition had to be made. For example, the forms of the North Indian pieces had to be substantially shortened in order to achieve an overall balance with the medieval works. Also, a studio environment was chosen as the recording venue; this allowed an overall balance between the variety of instruments, but also resulted in a less than ideal acoustic space where all the subtle components of the ecclesiastic chant could develop. But only in these ways was it possible to bridge the gaps through which the differences as well as the common aspects of North Indian music and the early music of the Occident could be made audible and tangible.

Dominique Vellard’s musical interests have their roots in his early experience as choir boy at Notre-Dame de Versailles. His teacher there, Pierre Beguigne, sparked his interest in Gregorian chant, the polyphonic works of the Renaissance, the French composers of the seventeenth century, and in Johann Sebastian Bach. After studies at the Versailles Conservatoire he began to delve into Baroque music, but was soon drawn back to the works of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, which corresponded more to his means of musical expression. Besides an intensive occupation with contemporary music (for example, in collaboration with Marie-Pierre Brun, Eugene Ferre, Jean-Pierre Leguay, and Jacqueline Ozanne), he also devoted himself oriental (or eastern) musical traditions. In addition to learning elements of North Indian music with Ken Zuckerman, he collaborated with Aruna Sal-ram (South Indian singing), Yann-Fanch Kemener (Brecon gwerz), and with Francoise Atlan (Sephardic traditions). Since 1982 Dominique Vellard has taught voice in the medieval department of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, and has given courses on a regular basis at the Conservatoire National Superieur de Musique de Lyon since 1988. He is the founder and director of Ensemble Gilles Binchois, and since 1991 artistic director of the festival “Les Rencontres Internationales de Musique Medievale du Thoronet.” Over thirty LPs/CDs, many of them recipients of awards, testify to his many-sided musical personality.

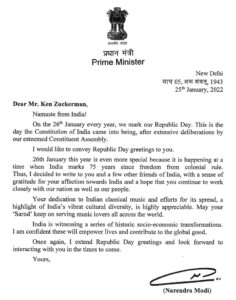

Ken Zuckerman was born in the USA, and is considered one of today’s most skilled sarod players. He has studied this 25-stringed plucked instrument for over thirty years with the renowned Indian master Ali Akbar Khan, and has also accompanied him – the first western musician to do so – on many tours through India, Europe, and the USA. On his own concerts throughout the world, Ken Zuckerman performs with some of India’s finest tabla players, including Swapan Chaudhuri, Zakir Hussain, and Anindo Chatterjee. He directs the Ali Akbar College of Music in Basel, Switzerland, and teaches North Indian classical music at the Basel Academy of Music. As a lutenist he was a pupil of Thomas Binkley, Eugen M. Dombois, Paul O’Dette, and Hopkinson Smith. He is known especially as an expert in the field of improvisation in medieval music. Since 1980 he has taught this subject at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, and also made several recordings on lute. Ken Zuckerman’s longterm training in composition and improvisation, both in Western and Indian music, has also enabled him to take part in various classical and experimental ensembles. These include Diaspora Sefardi (Hesperion XXI, dir. Jordi Savall), India meets Persia (with Hossein Alizadeh), and Modal Tapestry I and II (2000/2002), with members of the SWR Symphony Orchestra Baden-Baden and Freiburg).

Swapan Chaudhuri is one of the most outstanding and well-known tabla players in the North Indian classical tradition. Encouraged by his family, he began playing tabla at the age of five, and later continued his training in Calcutta with Pandit Santosh Krishna Biswas. Since completion of his studies (Master of Music) and numerous awards from the Indian government, he has not only developed into a top ranked soloist, but also an accompanist to the most famous performers of Indian music, including Ali Akbar Khan, Ravi Shankar, and the late Nikhil Banerjee. Swapan Chaudhuri has been guest professor at various American universities, and is on the faculty of the California Institute of the Arts. He lives in California and is director of the percussion department of the Ali Akbar College of Music, both in San Rafael and Basel. Numerous CD, radio, and television recordings document his artistry.

Keyvan Chemirani (born in Paris) began studying the Iranian zarb at the age of thirteen with his father, from whom he learned the traditional percussion techniques. He later earned a degree in mathematics and since then, has pursued a career as a musician, both as a solist and in ensembles. His versatility has led him to collaborations with representatives of traditional Persian music, Ottoman music, Greek and Turkish music, and the Spanish-Sephardic tradition, as well as with jazz musicians and musicians working in the area of contemporary improvised music, including David Hykes, Albert Mangelsdorff, Michel Bismut, Carlo Rizzo, Michel Montanaro, Jorge Pardo, and Jean Marc Padovani. His playing can be heard on numerous CDs, including recordings with his father and brother in their family trio. back